I’ve always had a fascination with the South. I’m not a native of the place at all, but something about the contradictions and variety of the region has always interested me. As the summer closes out and the chill of fall settles in, heading south also becomes a more pleasant prospect for those of us on two wheels. The summer stretches just that little bit longer every mile you head closer to the equator, and when it might be too chilly to ride north of DC, it’s still pleasant the other way.

So, in an effort to get out of the house on a long weekend, I packed up my tent and side cases, and resolved to get a little southern tour in, all on a fairly tight time budget of three days.

After taking care of a bit of work on Friday morning and getting my R65 all loaded up, oil levels checked, and gas tank filled, I hit the road and aimed for balmier climes. Since I left relatively late in the day, around noon, time was of the essence, so I took the highway. Somehow 95 is the worst of both worlds, always either too fast or too slow. When traffic’s actually moving, the wind buffeting and sharing the road with semis is always unpleasant, and then because 95 is forever congested, the rest of the time you’re crawling along at 10 miles an hour and feeling your clutch hand start to cramp. All said though, the highway system isn’t very interesting to look at, but it sure does move you effectively from place to place. Six hours saw me get from DC down across the North Carolina state line and rolling into Kitty Hawk, the birthplace of powered aviation.

A bit tired and achy, I rolled into a private campground, paid a little too much for a campsite, and set up my tent in some grass next to a little dock, with the sound of water lapping against the pier. With camp set up and the daylight fading, I hopped back on the bike and rode over to the ocean. The moon was out and bright, and as the sun went down, its blue light reflected on the wide expanse of the Atlantic. It really doesn’t matter how many times you see the ocean, it always remains mesmerizing.

The next morning, I packed up all my stuff and headed out of the campground. After a quick breakfast at a local diner (tagline: Eat and get the hell out!) the goal for the day was to ride all of the Outer Banks. I first stopped off at Jockey’s Ridge State Park, which is home to the tallest living sand dune environment on the Atlantic coast. Apparently it’s a popular spot to do some hang gliding or sandboarding, but since I was there early in the morning, I mostly trudged through the shifting sands alone. In the huge expanse of the sands and the sky, you can get the slightest sense for how people might go insane when lost in the desert.

Back on the bike, it was time to cover some mileage. I knew I had to get to the first ferry at 11, so I couldn’t dawdle for all too long. This section of NC 12 is a precarious road that cuts a thin line down between the Atlantic on one side and the Pamlico Sound on the other, ridged with ever-shifting sand dunes, and dotted with long bridges that connect one spot to another. Hurricane Ian, or what was left of it, blew through here somewhat recently and had evidently pushed tons of sand onto the road, as there was still plenty of heavy earthmoving equipment parked next to the side of the road, and you could see the sharp lines in the dunes that had clearly been moved. What this meant for a motorcyclist though, is that the winds would whip sand right off the top of the dunes to your left and send it flying across the road, which really sting your neck. I ended up having to pull over to put on a scarf just to protect my neck.

Not far down the Outer Banks, I stopped at Bodie Island lighthouse. Surrounded by pine trees on the way in, it’s actually the third iteration of the lighthouse in this general location. The first one was built on a bad foundation and had to be demolished in 1859. That same year, another was built nearby, but then retreating Confederate forces blew it up in 1861. The current lighthouse was finished and entered service in 1872 and has been keeping a quiet watch over the area ever since.

Back on the road, I aimed for the village of Hatteras, where I would catch a ferry down to Ocracoke, the other island on the southern end of the archipelago. Riding toward the ferry, I can’t help but marvel at the fact that people actually live here, which strikes me as a completely insane proposition. I can definitely see the appeal of life here, wide open beaches and beautiful weather and whatnot, but all at the price of being at the regular mercy of hurricanes, all on a little strip of land nary a half mile wide at the most points. All of this while the climate is changing and storms seem to be getting stronger and more frequent. I suppose some folks will always be more thrill-seeking than myself!

Following NC 12 down through Hatteras, the road ends. Here, the North Carolina Department of Transportation operates a free vehicle ferry on a really frequent schedule, sometimes with boats departing just a half hour apart, depending on the time of day. Being on a motorcycle gets you a bit of special treatment too! The steward saw me on my sand-blasted bike and told me to hop to the front of the line, where you wait at the front. I chatted with another one of the dock workers, who said that it really depends on who’s loading the boat—sometimes they put the bikes on first, sometimes in the middle, but you’re pretty much guaranteed a spot on the next ferry, regardless when you show up, which is pretty nice.

On the ferry, I put the bike on the sidestand, have a chat with another passenger about bikes—he tells me about his vintage Honda CB, and says he doesn’t have the confidence to do cross-country trips on it. I’m happy to have a little more confidence in my machine, but perhaps that’s purely naivety on my part. Either way, I’m happy to take this old machine out on the road where it belongs, or onto boats where it may or may not belong.

As the ferry powers us out into the Pamlico Sound, I see fishermen wading in the sound with massive poles, probably after red drum or other fish, as pelicans fly over the water and a friendly dog pokes his head out the truck that’s parked in front of me. The crossing takes you in a wide U around the Hatteras Inlet, and a crab-spawning sanctuary between the islands of Hatteras and Ocracoke. On the way over, you get to watch a fair amount of seabirds and are subjected to the very loud engine of the ferry and its lovely smell of diesel.

After an hour and a half of sailing, you’re kicked off the boat at the eastern end of Ocracoke, where directions are no problem—there’s only one road, and it only goes one place, and that’s the town of Ocracoke itself, which is on the western end of the narrow, 15-mile long island. The island’s relative inaccessibility, only reachable by ferry or plane, makes it a fairly quiet space, with miles of sandy beaches facing the rough waters of the Atlantic with minimal presence of other tourists. On the Pamlico Sound side, a low salt marsh is a tangle of low-lying plants and thickets, and on the Atlantic side, the beaches are sandy and wide, with crabs and birds skittering about.

After 15 minutes of riding or so, the relatively untouched Atlantic coastline turns to a small, lively village, seemingly overrun with folks in golf carts—a sensible vehicle to have on a place like this. I had originally planned to take a longer ferry from here over to Swan Quarter, back on the mainland of North Carolina, but since it would have left me no time to actually poke around, I jettisoned that plan and decided I’d just go back up the way I came. With that decision made, I headed over to see a unique cemetery on the island.

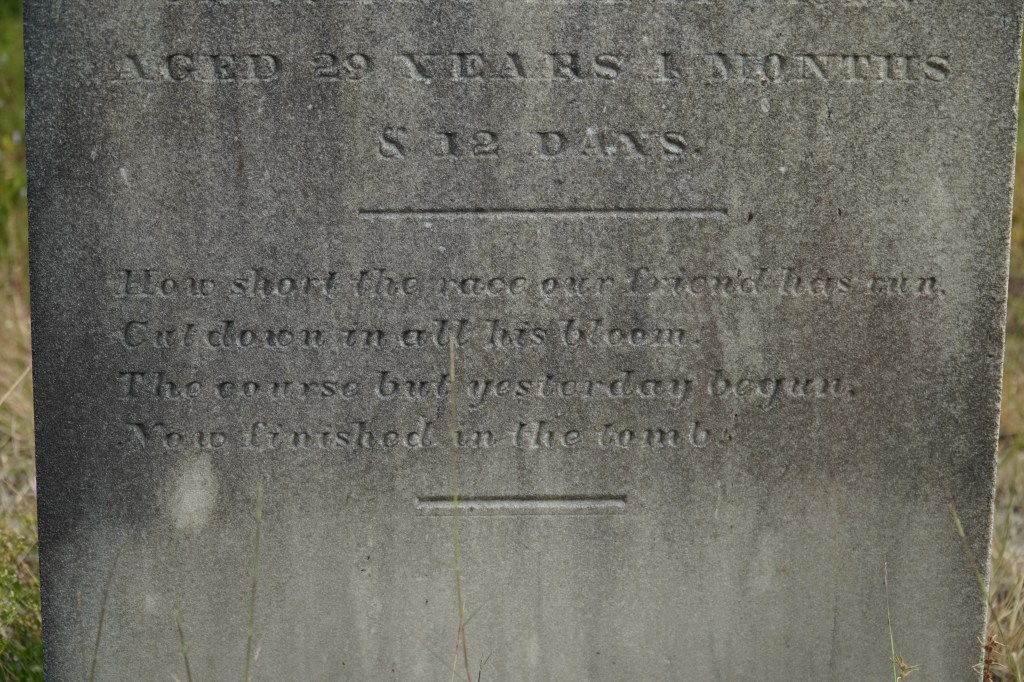

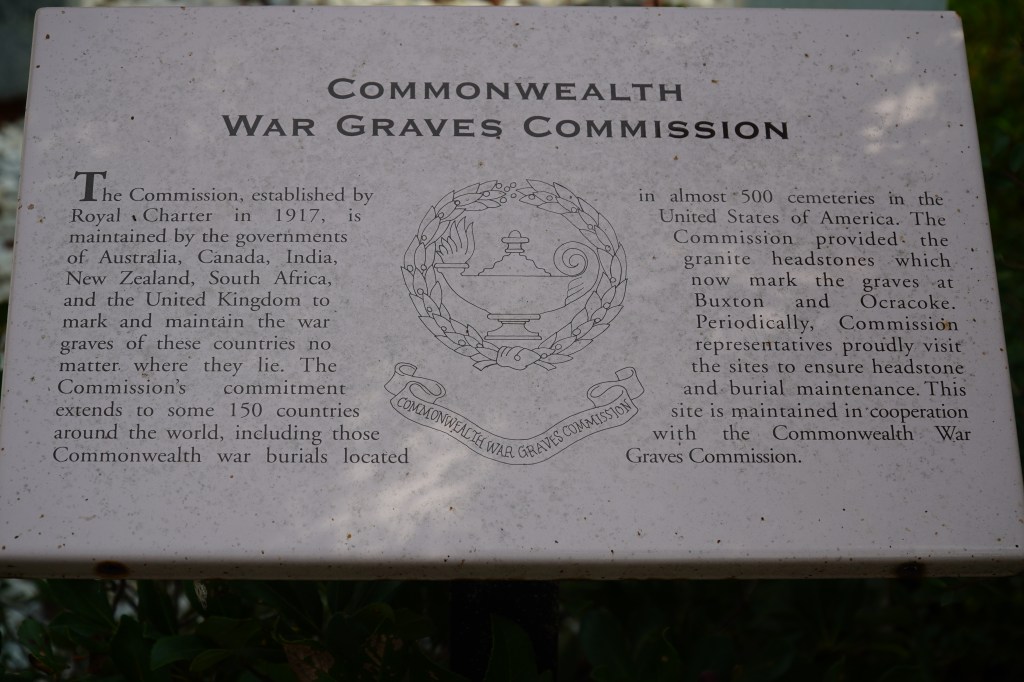

At the beginning of World War II, after the Germans had declared war on the United States, a small group of German U-boats were dispatched to the US eastern coastline to prey on merchant marine ships. At the time, the United States was woefully unprepared to defend against this, and a tiny group of German subs managed to sink nearly 400 merchant vessels. Burning ships off the Outer Banks were so bright, it was said you could read a newspaper at night. One such vessel, a British vessel called the HMT Bedfordshire that was patrolling the coast was torpedoed, ultimately taking the entire crew of 37 sailors with it. In the days following the sinking, four bodies of the crew washed ashore at Ocracoke, and the residents buried them in a local cemetery. Today, there’s a memorial to the ship and its crew, and NPS, the US Navy, and the British Navy hold a ceremony every year to remember the men. Next to the memorial is also a collection of graves that date back to the 1800s, many of which included small poems on the headstones, quiet reminders and epitaphs of those buried there.

After spending some time at the memorial, I headed over to see the lighthouse on the island. The Ocracoke Light Station is the second-oldest active lighthouse in the country, finished in 1823. The lighthouse survived the Civil War—though Confederate forces did pilfer the lenses—and operates to this day under the ownership of the US Coast Guard. By this point I was pretty hungry, so I got a shrimp burrito at a local Mexican place. I don’t think it counted as authentic Mexican per se, but it sure was delicious, honestly one of the better burritos I’ve ever had. At this stage, I had an eye on the time, because I did have a place to stay for the night in Plymouth, NC, back on the mainland. I had spent a bit of time at the farthest terminus of this particular adventure, and it was time to start the journey home. So I hopped back on the bike, and headed back where I came from, towards the ferry back to Hatteras.

On the ferry back, I was at the very end of the boat, right above the engine and it was loud as hell, with the motor making a good bit of racket and then all the loose metal parts of the ship vibrating aggressively along with it. I ended up sticking my earplugs back in just because of the noise. The trip back across was considerably rougher than the first passage, and I had to have a hand on my bike the whole time just to ensure it stayed firmly on the ground. One particularly large swell had me have to hold the bike down on the kickstand after it did its best to fall over. Behind the boat, the sea birds followed along, looking for fish that might be churned up in the wake of the boat in the relatively shallow water.

Back on Hatteras, I headed north again. I stopped for a coffee and a snack at a local coffee shop just to get a bit of caffeine in me for the few hours of riding I had left. Looking at the temperatures, I knew it would be getting a little chilly as I headed back west across the water and into North Carolina proper. The ride toward my stay for the night was beautiful though, riding across the bridge to the mainland, and then through the swampy marshland that’s near the coast. Little waterways branched off from where the road cut through the trees, and houses were hidden away behind mosses and mangroves, sitting on little stilts. As the sun went down, the outlines of the trees became sharper, and as I went further west, the scenery changed from swampy to more of an inland scene of pines. After the sun went down, I was getting pretty cold. It was probably around 50, maybe a little bit below, but by the time I got to the motel I was staying for the night, I was pretty thoroughly chilled. As much as I probably would have preferred to camp than to stay at a hotel, having access to a nice hot shower to warm up more or less changed my mind on that front.

The next morning, the air was still chilly and there was a good amount of condensation left on my bike from the evening. I packed up all my stuff, grabbed a quick bite to eat, and hit the road. I had about 300 miles to go to get home, up through the last bit of North Carolina and then up the entirety of Virginia.

This upper part of North Carolina near the Virginia border is agricultural, with fields of soybeans and tobacco and cotton. As I was riding along, I smelled something unfamiliar to me that smelled kind of like super glue or modeling glue. At first I thought something electrical might be giving up the ghost on my aging bike, but I realized as I rode along and the smell waxed and waned that it was just the smell of the cotton fields. I’m not sure if it was actually the cotton itself or a defoliant or pesticide sprayed on the bolls, but it was an odd smell, entirely unfamiliar to me. These fields of cotton were visually striking, creating a white blur as you ride the thin road through the fields, with little cotton balls floating in the breeze. I even saw a ginning facility that had large bales of cotton sitting outside the barns, having been recently wrapped up in big blue plastic for storage and, I suppose, transportation and sale. As something of a reminder of the sinister past of this crop, there were the rundown, dilapidated remains of sharecropper cabins along the road every few miles, collapsing rotten remains of the not so distant past when poor families were tethered to the land, and tethered to a life tending these spiky little plants. Riding through fields of cotton is certainly visually beautiful, but I can’t help but feel uneasy around it. A field of cotton feels different than a field of corn or soybeans, maybe partially because I remember one from my childhood and not the other, but also because the history of this plant is more bloodstained than others.

Heading up through Virginia, I settled in for the ride home, not in a rush, but now in a place that was familiar to me, the rolling forests and fields of this state that I call home. As I rode past Richmond and on to the final stretch of backroads before hopping on the express lanes near Quantico, I thought about how nice it was just to take a break from normalcy and go somewhere where the sights and smells and sounds are just a little different from home. That’s one nice thing about living in this part of the country, you don’t have to go far for the colors and shapes of the scenery to change enough to keep you interested—and on a bike, it’s amplified, with the smell of salty sea air coming in through your helmet and the sand whipping your neck and the temperature dipping as you ride through low spots in the terrain. Sure there are other ways to spend a long weekend, but I’ll take this over most other options.