Getting to know the nation’s capital and its environs by riding to the four corners of Washington, DC

Many Americans have a strongly held conception of Washington, DC. Swampy, full of people working for special interests shaking hands in the halls of power, a city chock full of the worst of the grifter class. While it’s true that some of those people certainly exist, overall, the city gets a really bad rap by people who don’t live in it — DC is a vibrant, green city, covered in trees, dotted with wonderful restaurants, steeped in history, and mostly populated by regular people who don’t have anything to do with the federal government. It’s also a deeply imperfect place, as all American cities are. It’s a city simultaneously in pursuit of a better democracy, but also blighted by some of the nastier forces of American society, a place free and unfree at the same time. So to see it, I packed a few day items into the creaky touring cases of my 1980 R65 and set out to see the four corners of the city, the boundary stones — north, east, south, and west. And another west.

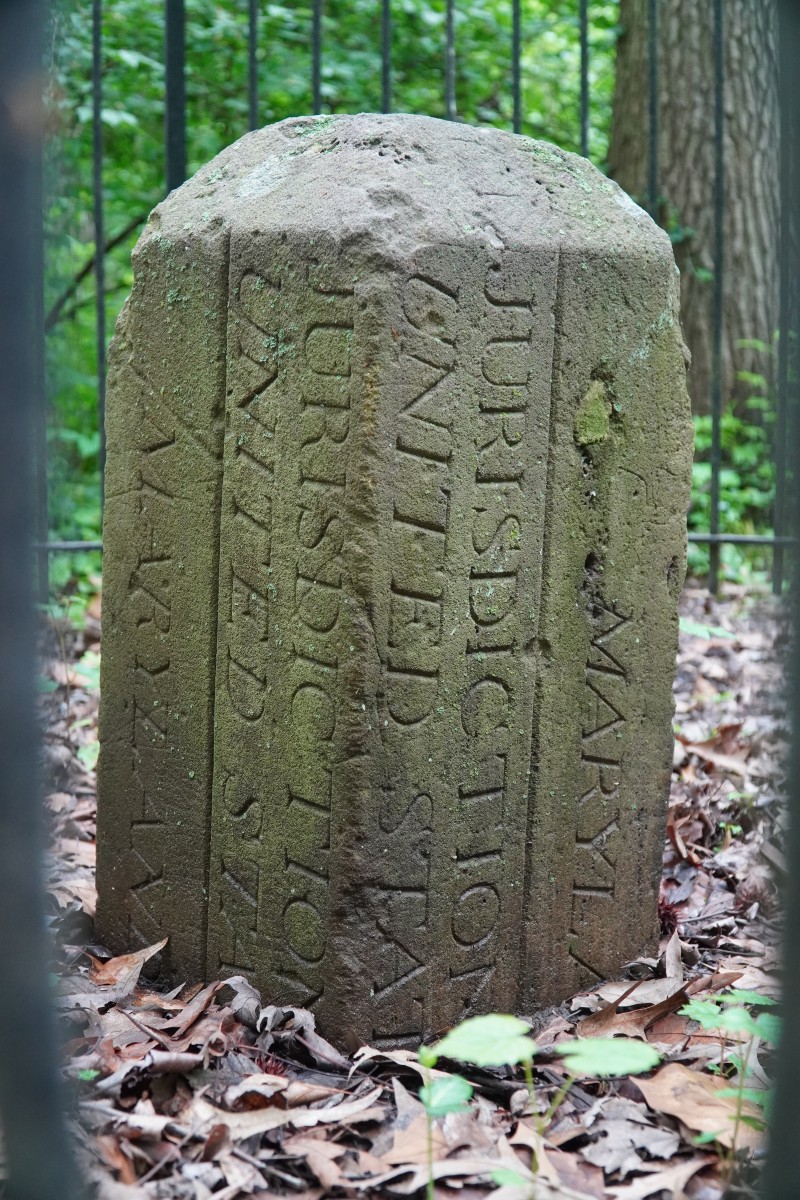

Washington, DC is something like a square, turned 45 degrees on its side, bordered on the southwest by the Potomac River. As I live in Pentagon City in Virginia, you would assume I’d have to head north or east first. But DC didn’t used to be truncated by the waters of the Potomac — to find the first, original 1792 boundary stone, I headed straight west, about seven miles further into Virginia to a shady spot in a sleepy Virginia suburb called Andrew Ellicott Park. Fittingly, the park’s namesake was a Revolutionary War veteran and surveyor whose team led the process of laying the boundary stones in 1791 and 1792, which now remain as the oldest federally placed monuments in the United States. The park itself is just a quarter acre with a few trees, a gravel parking lot so soft I nearly dumped my bike as the kickstand sunk into the ground, and the boundary stone itself, which sits surrounded by some metal fencing and a few small plaques. The stone, weathered from centuries of rain and missing a chunk of the top, now stands outside of the area it once marked — the Virginia side of the river was ceded back from federal hands to the state in 1847 after many years of debate about the disenfranchisement of its inhabitants, something that remains pretty relevant today.

With the first stone finished, it was time to head to the actual current-day western corner of DC, which doesn’t have a border stone, but is marked by the river’s edge. The ride from Virginia to that spot was pleasant. Even though it was a misty day and rain peppered the front of my visor, it was early enough on a Saturday morning that there wasn’t much traffic, and the gentle rolling hills that surround the river make for nice, undulating roads. Once across Chain Bridge, to actually get to the river, I had to park on the side of the road, squeezing the bike in between haphazardly parked cars, and then walk down some stairs, up the C&O Canal trail for about ten minutes, and then down a slipway into the woods to the river. It had been raining recently and the river was way above its normal banks, churning an angry brown as it ripped silt up from the bottom on its way to the Atlantic. Standing on the Belvedere Viewpoint, looking up the river, the far western corner of the District is sitting somewhere on the mucky far bank. Even if there was a boundary stone, I don’t think I could have gotten to it.

Back on the bike, it was time to head north. On the way, I stop by the National Cathedral just to putter around and admire the building. It’s under a bit of construction at the moment, but it’s still an impressive edifice. Thankfully, one of the nicest roads in the DC runs north and south, so it was time to head to Rock Creek Park. The park, designated in 1890, was the third national park ever designated by the federal government, and it serves as something of an oasis. Its 1,700 acres run in a serpentine shape north and south, and the parkway that runs through it has nary a patch of straight road. Although during the week it can be chockablock with traffic, on weekend mornings, it’s a good spot for the local two-wheeled denizens to get out and zip through some corners. I wasn’t the only airhead out either — as I was on my way through the park, I spotted a fellow airhead with a sidecar headed the other way, though I didn’t get a close enough look to know what model it was.

Out of the park, it’s only a few miles up another of DC’s tree-shaded parkways to get to the northern boundary stone, just outside Silver Spring. The stone sits in a place of no renown, directly adjacent to the rocky drainage ditch for a local apartment complex. It has no parking lot of its own and no real plaque except one that’s attached to the fencing noting that it’s the north boundary of the District of Columbia. Honestly it seems fitting, as if you didn’t know the boundary was there already, there’s little indication that anything changes as you go from the northern reaches of the District into Maryland, except maybe for the fact that there’s more Maryland drivers — a dangerous proposition.

From Silver Spring, I get back on the bike and head southeast. On the ride to the eastern corner of the District, one gets a tour of one of the less pleasant aspects of life in DC. The eastern portions of the city are generally disadvantaged, and as you ride from the fairly affluent northern Maryland exurbs across the Anacostia River, the roads get bumpier, with more potholes, and you find yourself being more active on the handlebars to stay on the good tarmac. Every once in a while you feel your suspension bottom out on a pothole despite your best intentions. On the way to the east corner, you see the way the city allocates its resources, just what kind of DC resident gets the shiny buildings and the clear sidewalks and the fresh road surfaces. It’s one thing that’s always made me deeply uncomfortable about the city, it’s a deeply stratified place, with ambassador’s mansions on one end and rundown houses with loose bricks and broken shingles on the other.

I round a bend and haul the bike up on its center stand on a residential street and walk down a small, wooded trail across the street to find the eastern boundary stone. It’s in a tiny grotto, surrounded by a fence like all the others, living out its life its quiet obscurity. I take a picture and walk back to the bike.

At this stage, only one corner remains. I drag the bike off its stand, fire it back up to hear that happy two cylinder purr, and then set off back through the neighborhood, and down a short highway stretch towards the bridge to Alexandria. The Woodrow Wilson Bridge runs from National Harbor — a small hub of casinos and hotels and various other garish, neon-colored, lifeless things — to the city of Alexandria, which once represented the southern tip of the federal city before the aforementioned retrocession of the land in 1847. Alexandria is a city with a tight street grid, some cobbled and brick streets, and charming rowhouses, dotted with small shops and restaurants. Historic housefronts have been maintained for decades, helping keep the city’s quaint sensibilities. After getting off the bridge, I make the mistake of turning onto a cobbled side street, which makes for a deeply unpleasant, bouncy ride for a city block before I get to the next street and head off on pavement again.

Underneath the huge pillars of the bridge, I haul my bike up on the center stand one more time, and then wander down the trail at Jones Point, where the last cornerstone on my visit is waiting. It’s the last one I’m seeing, but it’s the first boundary stone to have been laid. Incidentally, it’s also the first federal monument ever to have been constructed. In 1791, a free African-American surveyor named Benjamin Banneker set it in the ground as the start of the surveying project that laid each one of the stones I’d already visited, laying out the territory of what was then the new federal capital. Today, the stone sits next to a squat, white lighthouse, and is protected under a glass roof and stone sides, as the water of the river lapping against the shore has threatened to steal away the very ground it’s laid upon.

And with that, my trip was at an end. A completely arbitrary one, and it only took about five hours, but it gives you a little glimpse into DC. Part leafy parks, part beautiful architecture, part rundown neighborhoods left with few resources until they’re gentrified out of existence, and part historical places, steeped in stories from centuries gone by. An incomplete picture of the city, but a good snapshot to be seen on two wheels.